About 'ms office 2007 product key'|buy microsoft office 2007 software windows xp

It can be amusing, and sometimes even instructive, to observe the way criminal justice is presented in old popular entertainment-interrogations in pre-Miranda days, for example, or police pursuits before the "fleeing felon" standards were overturned in the 1980s. In the winter of 1984, the popular television series Dallas presented a storyline involving a government employee named Edgar Randolph, who was being pressured by the series' arch villain J.R. Ewing to reveal classified information on government oil leases. J.R.-presented then, as always, as the "bad guy"-threatens to disclose a sexual offense against a child for which Randolph had received therapy in his adolescence. It is interesting to note, a little over two decades later, that the storyline would be impossible to broadcast today. Leaving aside the near impossibility of depicting any sexual offender in anything other than a diabolical light, J.R. would be irrelevant, as his role has been filled by our own public leaders, ostensibly acting in the public interest. The national outpouring of revulsion at lurid sex offenses (especially those involving child victims) that culminated in the establishment of public sexual offender registries in every state has not abated, and as of this writing the federal government has climbed on the bandwagon by creating a national registration system with conditions that are considerably more severe than those of many states. It is the main purpose of this work to critically examine the sex offender registration system as it now exists-in some form-in all fifty states. The arguments presented here are those least likely to be heard in most public venues, for they cut against the grain of the national zeitgeist, and challenge what can arguably be called manufactured public opinion. Nevertheless, it is critically important to consider these arguments, for they call into question the desirability of the continuation of this system. As a reflective and humane society, we owe it to ourselves to consider whether the social experiment on which we are relying to keep us safe has instead become a punitive scarlet letter or worse: an invitation to open criminality. This article grew out of the author's undergraduate thesis as a student at Madonna University. The methodology used in creating it involved a survey of online sources concerning Megan's Law and associated issues--most of which have sprung up in the past five to ten years as the drive for registration and community notification has accelerated--followed by a survey of available professional and popular literature, which is available in copious quantities on the subject of sexual offenses. Because a major concern of this report is the problem of sexual offending as perceived by the public, popular media sources are often cited. I would like to acknowledge and thank Geoff Birky of Ethical Treatment for All Youth for his suggestions and encouragement in producing the article. Geoff's excellent work in exposing the legal and psychiatric abuse experienced by young people mislabeled as sexual offenders has been filling a badly neglected void for a number of years. II. Emergence of the registration system. Child sexual abuse, once ignored or spoken of only in hushed tones, first emerged as a serious criminological and public concern as a result of publicity given to child pornography rings in the late 1970s. The 1980s saw an increase in television coverage given to the problem of molestation by acquaintances or caregivers, and for a time, coverage of allegations of organized child sex abuse became prominent. The notorious McMartin and Fells Acres day care cases served as sensational press fodder, though both were investigated in a professionally and ethically suspect manner and resulted in numerous false charges and, in the latter case, dubious convictions. In 1993-1994 this history repeated itself with a sensational city-wide scandal in Wenatchee, Washington in which forty-three adults were arrested on an incredible 29,726 charges of sexual abuse involving sixty children. The overwhelming majority of the charges were later determined to be baseless (Schneider et al., 1998). And, in 1993, U.S. Attorney General Janet Reno used allegations of ongoing sexual abuse to justify her decision to force the surrender of the armed Branch Davidian cult near Waco, Texas, an action which resulted in some ninety deaths. (Janet Reno has a documented history of shabby opportunism and fanaticism on issues of sexual abuse that deserves its own essay. Alas, time and space constraints do not allow us to undertake a thorough plumbing of the depths of Reno's record.) Emerging from this atmosphere of increasing militancy in confronting the sexual abuse problem, the current era dates from the special revulsion of the public in the early 1990s to the sexually motivated murders of child victims Polly Klaas in California and Megan Kanka in New Jersey. The Kanka murder in particular created feelings of disbelief among the public, as her killer was a convicted sexual offender living in the victim's neighborhood. Within three months of her murder in 1994, New Jersey responded to public outrage with the first "Megan's Law", mandating a system of community notification of the whereabouts of convicted sexual offenders, on the premise that such a system would better protect the state's children. The Megan Nicole Kanka Foundation, formed to promote Megan's Law throughout the U.S., avers in its purpose statement that "Every parent should have the right to know if a dangerous sexual predator moves into their neighborhood" (Our Mission, 2005). Few voices were heard at the time suggesting that any unintended consequences might ensue from the new experiment; one notable exception was sexual offense expert Robert Freeman-Longo, who will be mentioned later. The federal government's Jacob Wetterling Act of 1994 and a supplementary act in 1996 essentially made Megan's Law a federal mandate, but this was almost a redundancy; most states were already rapidly following New Jersey's example in establishing sexual offender registration, including Michigan in 1995. III. General perceptions of the American population regarding sexual offenders In order to understand the attraction that community notification laws hold for members of the public, especially parents, we must first consider some of the views about sexual offenders that are commonly held, particularly those that are questionable or inaccurate. The first of these perceptions is that sexual offenders are incorrigible; that neither punishment nor treatment will induce them to avoid re-offending. New York. Assemblyman Jim Hayes, arguing in favor of across-the-board "civil confinement", recently claimed that sexual offenders have a re-offense rate of "nearly 100 percent" (Hayes, 2005). In this claim, he follows another state legislator, Pennsylvania's Beverly Mackereth, who offered the more modest figure of 98 percent in a 2004 article (Joyce, 2004). Other public figures and politicians, while not always providing such bizarre and unsourced statistics, have contributed to the public's belief that the recidivism rate among sexual offenders is so much higher than that of other categories of criminal offenders that the treatment of sexual offenses as a unique category of crime is warranted (Lotke, 1997; Levine, 2002). To further shore up this perspective, it is often argued that social science has established that "nothing works" when it comes to therapy for sexual offenses (Lotke, 1997). Another premise on which the public often bases its fervent support for registration is the frequent conflation of sexual offenses with violent ones. A "bait and switch" technique is employed, in which the most lurid sexual crime in the headlines at the moment-usually a murder-is offered as representative of sexual offenses in general. This identification of sexual offenders with rapist-murderers is often packaged with the implicit or occasionally explicit corollary that sexual offenders are to be seen as proper targets of violence. Doug Giles, a right-wing syndicated columnist, is not the most well known pundit to jump aboard this particular bandwagon, but he is one of the most extravagant. Giles published a column in April 2005 which began by mentioning the recent murders of child victims Jessica Lunsford and Sarah Lunde, and ended by advocating the death penalty for sexual offenders; not rapist-murderers in particular, but sexual offenders. His column, being perhaps the first in recent times to demand a literal return to lynch law, is worth quoting at length: Let's make [registered sex offenders] shake in their boots...Let's get the local TV news to run dailies of their faces and the places they inhabit. Let's get the newspapers to have a special sewage section dedicated to showing and keeping tabs on them. Let's put HazMat signs in the front yards where these creeps live....Let's force them out of our communities and let them get their own place where all of them can feel at home and not be judged, and where they can do the dirty deeds to each other. I know a perfect place; it is 666 Lucifer Lane, close to the river Styx on Dante's second concentric circle. And I'm positive, positive, there would be a lot of people available to help get them there (Giles, 2005a). What makes this descent into psychopathology by a normally respectable conservative writer explicable, if not justifiable, is the writer's apparent identification of the categories "sexual offender" and "child rapist-murderer." In November 2005 Giles offered a less blood-curdling but equally paralogical repeat performance in an attack on the American Civil Liberties Union, identifying the murderers of Jeffrey Curley with the general population of registered sex offenders (Giles, 2005b). A further common belief held by many in the public-and by those to whom the public looks to interpret events, the news media-is that when a sexual offender is apprehended and convicted, they frequently face a mere 'slap on the wrist' from the justice system. News commentator Bill O'Reilly recently claimed "You can rape a child [in New Hampshire] and some loony judge can give you probation" (Kentucky Community and Technical College System, 2005), trading on the violent connotation of the word "rape", and not troubling to mention, of course, when any such thing has happened in New Hampshire. IV. Inadequacy of these perceptions Is the purple prose of these increasingly militant, even hysterical voices to be taken as a sound basis for public criminal justice policy? The Michigan cases of teacher Brian Corbitt and teenager Justin Fawcett may provide a partial answer. In late 2002, in lame duck session, the Michigan legislature passed a substantial tightening of the state's criminal sexual conduct laws. Among the changes enacted was the elevation of the age of consent in relationships involving schoolteachers and their students from sixteen to eighteen years. The act went into effect in 2003 with little fanfare-too little fanfare, it would appear. At the time, Brian K. Corbitt was a high school teacher in Homer, Michigan, in his mid-twenties. He engaged in a sexual relationship with a sixteen-year-old student and thus became the first person prosecuted under the new law. Despite having no criminal record and having been unaware of the recent alteration in the age of consent, a sentence of six to fifteen years was recommended. Corbitt wrote to Judge Conrad Sindt "I do not think I can survive a prison sentence." On the morning he was to be sentenced, Corbitt was found hanging in his mother's garage, a victim of suicide (Christenson, 2004). While it appears to have been the prospect of incarceration and not that of registration that precipitated Corbitt's self-destruction, it can be argued that the case does belie the common public perception of what qualifies as a sexual offense. Justin Fawcett was an eighteen-year-old from Oakland County, Michigan who pled guilty to the crime of seduction based on the revelations in the "teen sex diarist" case of 2002. The diarist was a fourteen-year-old girl who chronicled consensual sexual encounters with twenty-two boys and men. Eventually five young adults were prosecuted for participating in the liaisons, and the cases ended with the county prosecutor sensibly negotiating a plea bargain on the reduced charge of seduction. One reason offered for charging the men under the seduction statute was the general agreement that their offenses did not warrant the additional intrinsic burdens and humiliations of public registration. In early 2004 it was ruled by the Michigan Supreme Court that Fawcett's name would be registered, negating his contrary plea agreement. Fawcett's life began a downward spiral that ended in his death of a drug overdose on March 3, 2004. His untimely end did spur the Michigan legislature to enact a small but needed reform to the state's registration system, permitting young registrants in certain cases to petition for their names to be removed from the registry (Householder, 2004). What can we learn from these examples? Among the many commonly held assumptions that underlie, and explain, the typical American view of the sex offender is the facile notion that every sexual offense creates a traumatized victim; and further, that the offender is fully cognizant of this and therefore responsible for the trauma. This notion is easily disproved by even a casual consideration of the headlines. In the Corbitt case cited earlier, there is no reason whatever to suppose that Brian Corbitt's lover was traumatized by their relationship-a relationship that would've been legal a year earlier, would've been legal in a number of other states, and would've been legal had Corbitt been in almost any profession other than education. On the other hand, it would be absurd to believe that she has been unharmed by the consequences of the ruthless enforcement of an ill-advised law. Indeed, in such cases as the increasingly popular use of police decoys in trapping would-be sexual offenders online, no victim, traumatized or otherwise, exists at all. (It is worth noting that Maryland's highest court has disallowed this latter practice) (Kunkle, 2005). It is also not widely known that states such as Minnesota and Missouri include in their state "sex offender" registries persons never convicted of any sexual offense even as the term is understood legally. In Gunderson v. Hvass (2003), a registrant who was exonerated of rape but convicted of physical assault was denied relief from Minnesota's requirement to register. He was required to register because he was convicted of a crime "arising out of the same set of circumstances" as the discredited rape charge, and the U.S. Eighth Circuit Court of Appeals ruled that since the registry was a "non-punitive" and "regulatory" action, the presumption of innocence did not attach. The Missouri registration system has also come under increased scrutiny of late. It has been amended at least four times since originally being enacted in 1994; the ever-changing rules have resulted, among other problems, in many registrants not knowing they were registrants and even that they'd had arrest warrants issued for failure to register. Many were told, prior to the original enactment of the law, that their criminal record would be expunged with a plea bargain. One source reports a father being listed on the registry for pleading to misdemeanor child abuse for administering a spanking to his own child with a belt, which became a legal issue only as a result of a bitter divorce (KMBC, 2005). (A lawsuit on the constitutionality of the Missouri registration system was settled in 2006, with the Missouri Supreme Court permitting most regulations while striking down some of the law's "retroactive" provisions.) The "slap on the wrist" myth must be answered as well. Many public figures, including the above mentioned Bill O'Reilly, appear to have adopted the curious idea that sexual offenders are actually favored by the justice system-and occasionally they will point to an outrageously atypical case to illustrate their point. It is never mentioned by the same critics, of course, when an arguably excessive sentence for sexual misconduct is handed down. In 2004 ex-police detective Edwin Mann of Orlando, Florida received a twenty-six year prison sentence for a consensual sexual relationship with a fourteen-year-old girl. Barely one year later, two central Florida residents (John and Linda Dollar) were convicted of physically abusing five of their seven adopted children thus: The five children were so severely underfed that twin 14-year-old brothers weighed just 36 and 38 pounds each -- about 80 pounds below normal. Police compared their conditions to victims of Nazi concentration camps....Prosecutors said the couple also tortured five of the children, ages 12 to 17, with an electric cattle prod and bondage equipment. One of the children told police his toenails were ripped off with pliers (Reed, 2005). In contrast to Mann, the perpetrators of this (at least apparently) non-sexual crime each received a sentence of fifteen years' imprisonment, suggesting that the 'slap on the wrist for sexual offenders' theory is as much an urban legend as the habitation of the New York City sewers by alligators. The number of similarly disparate sentences between crimes of consensual sex and crimes of barbaric violence is unlimited; but it seems sufficient to rest the point on this example, as it is doubtful that commentators like O'Reilly actually believe what they are saying. (In a development worthy of the pen of Kafka, it was reported in late 2005 that John Dollar had offered "religious guidance" to accused child-killer John Evander Couey while both were incarcerated in Citrus County (Perez, 2005). V. Reasons for the inadequacy The origin of the lack of public insight into the problem of sexual offending begins with a serious misunderstanding of the definition of key terms on the part of the public. The language employed by those intent on tightening restrictions on all sexual offenders is often imprecise and emotive (i.e. "predator") or incorrectly employed (i.e. "pedophile.") We will consider the latter example for the moment. The discipline of psychology recognizes pedophilia as a pathological condition involving the persistent sexual attraction of an adult to preadolescents. It is commonly accepted by many mental health and criminology experts that pedophilia is a condition that is extremely difficult, or impossible, to cure-a conclusion which we may stipulate as true for the sake of the present analysis. It is apparent from listening to the use of the term by much of the media that the word's colloquial usage is more politically serviceable than scientifically sound. In the first place, a medical diagnosis of pedophilia is not interchangeable with the legal category of sexual offenses (or even "sexual offenses involving child victims"); one may exist in the absence of the other. Sexual offenders with child (i.e. underage) victims may offend for reasons other than suffering from a psychopathological condition of pedophilia. For instance, an offender convicted of consensual sexual relations with an adolescent victim would not be diagnosable as a pedophile (or, necessarily, as a member of any other pathological category.) On the other hand, even offenders with preadolescent victims may offend, not due to a pedophilic orientation, but because of opportunity, curiosity, or occasionally even revenge against the victim's parents (Lanning, 2001). Finally, not all sexual offenses have child victims; forcible rape of an adult and public indecency with an adult are sex crimes, but obviously not evidence of a pedophilic psychosexual condition. Therefore, a proposition that is true with respect to pedophiles as a group will not therefore be true of the much larger general population of sexual offenders, except by coincidence. Second, there is a false unstated premise at work to the effect that a recidivism rate equals the inverse of a cure rate. In reality, there are a variety of reasons a person who is not cured of an underlying condition may not re-offend-whether for reasons of conscience, lack of opportunity, or fear of the consequences. To employ a close analogy: alcoholism is not considered a curable condition, but it would be patently absurd to claim that no alcoholics remain sober. The combined effect of these two misconceptions has been to transmute the arguably true proposition "Pedophilia has a very low cure rate" to the demonstrably false proposition "sexual offenders have a very high recidivism rate," and the corresponding public belief that whatever is done to sexual offenders to protect the public from their incorrigibility is no more than they deserve. Owing to this confusion (and to the human race's perennial desire for scapegoats) sexual offenders remain, even to a greater degree than terrorists, the single group about which one can say literally anything and be believed. The number of sources that could be employed to discredit the 'universal recidivism' theory could easily overwhelm this article. It is therefore necessary to focus on a few of the most pertinent ones. In 2003, a major report was issued by the U.S. Department of Justice concerning prisoners released in the United States in 1994. According to this study, the rate of reconviction of released sex offenders for a new sex crime over a three-year period was 5.3%--with a reconviction rate of 3.5%. (It must be admitted, of course, that a three-year recidivism rate is far from the same as a lifetime recidivism rate.) The overwhelming majority of new sexual offenses committed by the parole prisoners were committed by those in the non-sexual offender category (Bureau of Justice Statistics, 2003). The records kept by the Michigan parole board from 1990 to 2000 also tell a drastically different tale than the commonly accepted one. According to its statistics, sexual offenders have the second lowest recidivism rate of any category of crime--the first being homicide. Fewer than seven percent of paroled sexual offenders commit a new crime, and in fewer than half of those instances is the crime another sexual offense. (It may be objected that there is a built-in bias in parole board statistics, since-if the parole board is competent-recidivism of parolees should be less than recidivism of parolees plus inmates whose sentences have expired without parole. But as this bias operates to some extent for all offense types, it is probably of minimal significance.) In 1997, researcher Eric Lotke identified three discrete studies that placed sexual offender re-offenses over extended periods of time in the teens (i.e. under 20 %.) One would express this conversely by saying that over 80 percent do not re-offend-almost the diametric opposite of what is typically heard in public discourse on the subject. Lotke's view of the re-offense statistics has been supplemented more recently in a Canadian study (a study on the relationship between age and recidivism) that found average recidivism rates below twenty percent in all offense categories (Hanson, 2001). In regard to the view that no sexual offender therapy works (except "castration", as the late mental health non-expert Ann Landers helpfully recommended in 1995), this idea is largely traceable to the findings of researcher Lita Furbe and those of the U.S. General Accounting Office (GAO), which found re-offense rates similar for treated and non-treated sex offenders, and concluded on this basis that treatment was ineffective (Lotke, 1997). The GAO study cautioned that "more work was needed before firm conclusions could be reached" (GAO, 1996). Yet in contrast to the fatalism that is heard from public authorities, the Institute for Psychological Therapies has been successfully employing cognitive therapy for many years in treating sexual pathologies; and a study from Vermont documented a three-year re-offense disparity of 8.2 % to 4.6 % for untreated and treated offenders, respectively (Lotke, 1997). In addition to the above factors, the lack of attention paid to the unique problem of youthful offenders gives the public a false impression of the problem. "Youthful" offenders does not merely mean young adults such as Justin Fawcett; in many states, including Michigan, Kansas, and Iowa, it may include minors whose crime involved consensual experimentation with age-peers. The psychiatric abuse experienced by many of these children has been well documented (Garfinkle, 2003; Zimring, 2004); and, in an ironic twist, among the other disadvantages of community notification is the inability of persons in many states to "live down" an incident which may have happened when they themselves were legally too young to consent to sexual activity. In Utah, a 13-year-old girl was impregnated by her 12-year-old boyfriend; both were convicted of sexual abuse and both were required to register as sexual offenders (Associated Press, 2005). VI. Vigilantism Human Rights Watch, via its U.S. Program, is currently conducting research about state sex offender registries. The research is specifically focused on the broadness of the registries and the effect that widespread community notification has on the ability of registered sex offenders to find a place to live free from harassment and acts of vigilantism. Their concern is not a theoretical exercise in benevolence, but a response to actual conditions that have followed the drive for community notification laws (Carey, 2005). One of the frauds perpetrated on the public by advocates of community notification laws has been the supposedly non-troubling placidity of the public response to registrants. We have been repeatedly told that vigilantism is a phantom threat, and that the public is mature enough to take revelations of their neighbors' offenses in stride. Is this the reality in the United States? Vigilante activity against sexual offenders, whether convicted, accused or merely suspected, did not begin with Megan's Law. But even many of those favoring the new community notification efforts began to acknowledge an acceleration in such activity by the end of the 1990s. A U.S. Department of Justice survey reported in 2000 that 83 per cent of Wisconsin registrants had reported being excluded from housing due to their registrant status; 77 per cent had experienced threats or harassment, and 3 per cent had experienced an actual vigilante attack (Zevitz, et al., 2000). This consistent with other reports from the same period. According to a British observer: On May 18, 2001, Judge J. Manuel Bañales of Corpus Christi, Texas, ordered 21 registered sex criminals to post signs on their homes and automobiles warning the public of their crimes, and the results were almost immediate. One of the offenders attempted suicide, two were evicted from their homes, several had their property vandalized and one offender's father had his life threatened, according to court testimony. Was Judge Bañales repentant? Not a bit: "They have only themselves to blame," he contended (Milloy 2001). One of the more noted instances of the justice system itself being transmuted into a tool of vigilantes was the case of Kevin Kinder of Tampa, Florida. After release from a total of nine years' prison and post-release civil commitment, the mother of one of Kinder's victims organized a movement to shadow Kinder from motel to motel, handing out flyers and drawing attention to his criminal history, even after having effectively expelled Kinder from her own county. Admitting openly that their goal was to maneuver Kinder into violating his parole, it was considered a cause for celebration when, after over a year of harassment, Kinder was sentenced to sixty years in prison for a series of parole violations. One of the violations based on which Kinder received a sentence three times longer than his original maximum sentence for rape was for disappearing from authorities- while hiding from the mob in his attorney's office (Goffard 2002; Goffard 2003). Florida Statute 784.048 provides that "In August 2003 convicted sexual offender and ex-priest John Geoghan was murdered in his prison cell in Massachusetts by neo-Nazi inmate Joseph Druce, who was serving a life sentence for murder. While there were a few shocked comments in the media at the time about the failure of security in the institution, it was shrugged off, in most quarters, as a predictable, if undesirable, instance of "jailhouse justice" in the words of state representative Demetrius Atsalis. It is noteworthy that Druce (subsequently convicted of murder in the incident) was confident enough in the moral acceptability of his crime to make a play for public sympathy, shouting at his arraignment "Let's keep the kids safe!" and "Hold pedophiles accountable for their actions!" (Associated Press, 2003). Finally, the manufactured hysteria came to its logical conclusion in a double-murder of two sexual offenders in Bellingham, Washington in August 2005. Previous documented murders of sexual offenders have sometimes been uncertain as to motive-they could plausibly have been revenge killings, underworld killings, etc. The Bellingham murders, however, were committed by a vigilante member of the public who selected their names at random from the publicly accessible sex offender registry, alarming even the local newspaper into a belated warning to avoid acts that might tend to undermine the public registry (Vigilantism threatens community notification, 2005). In the spring of 2006 another double-murder occurred when a mentally unbalanced Canadian murdered two sexual offenders in Maine. And, although it attracted little comment at the time, the short stories and recorded ramblings of mass murderer Cho Seung-Hui revealed an obsession with sexual abuse, and contempt for sexual offenders, only slightly more robust than that of Doug Giles and Bill O'Reilly. Cho raged in particular against John Mark Karr-an apparently delusional ne'er-do-well who'd never been convicted of a crime-and Debra Lafave, who'd never harmed a fly, but who gave an underage boy an orgasm. Cho's belief that homicidal violence was a proper and fitting response to sexual turmoil was not the product of his own disordered brain, but a belief in which this country is steeped, owing to the irresponsibility of the guardians of our culture. These developments were entirely predictable to anyone who has followed the news of the past fifteen years out of the United Kingdom. The violence and irrational barbarism toward sex offenders, whipped up by the tabloid press, reached its apex in 1994 with the burning alive of a young girl by inept vigilantes who torched the home of a sexual offender (Dodd, 2000). In other British instances, pediatricians have been threatened and assaulted by mobs who, unsurprisingly, didn't know the difference between "pediatrician" and "pedophile." To see in all these acts no more than random eruptions of unpredictable hatred is nonsensical. They are, on the contrary, the inevitable end result of a media culture which plays fast and loose with the facts, uses the most irresponsible propaganda imaginable, and leaves law enforcement-and the families of victims-to pick up the pieces when the panic they've created boils over into violence. But from the witch trials of Salem, to the red scares of the 1920s and 1950s, to the current sexual offender panic--there appears to be a recurring, cyclical need in American life to adopt scapegoats in order to validate the public's prejudices and fears. The technical term for this phenomenon is "moral panic" and we are now witnessing its bitter fruits. VII. Further costs to society of community notification laws The notable therapist and researcher Robert Freeman-Longo has identified a number of additional concerns that call into question the desirability of the community notification system. While acknowledging the reality and magnitude of the sexual abuse problem, and lauding the intentions of that favoring the existing system, Freeman-Longo believes that the goal of a safer society is not well served by the notification system. He has been among its persistent critics since its inception, noting the lack of deliberation in its passage and predicting social dislocations as well as the types of vigilantism documented above as a likely result of the new laws (Freeman-Longo, 1996). In subsequent publications, Freeman-Longo enunciated other objections to the community notification system. One is the financial cost to the community of maintaining the database, including the labor-hours required to verify that the public information is correct. The federal version of Megan's Law in particular operates as an unfunded mandate, requiring the cooperation of the state governments in return for federal money, but not providing additional funds to defray the cost of its implementation. Another collateral effect of the laws-and one almost certainly unforeseen by those who enacted them--is an increased unwillingness on the part of many victims and their families, as well as some professionals, to report abuse to the authorities: I have heard from a variety of professionals and child protection workers that they have been faced with the ethical dilemma of not reporting sex crimes perpetrated by youthful abusers in order to avoid the consequences these young people face from registration and notification laws. Many, in fact, have revealed that they have not reported some cases.... Reports from New Jersey and Colorado indicate that there is a decrease in the reporting of juvenile sexual offenses and incest offenses by family members and victims who do not want to deal with the impact of public notification on their family (Freeman-Longo, 2002). Also on the list of Freeman-Longo's indictments of the notification system is the ostracism faced by family members of sexual offenders; in at least one case, harassment of the offender's family and victim continued despite the fact that the offender himself was incarcerated at the time (!) VIII. Conclusion. It appears that some forces on the social and political scene have either learned little from the proliferation of hatred against those charged with any sex-related offense, or consider such a development beside the point. This should come as no shock, as moral crusaders are not normally given to analyzing their adopted issue in a nuanced manner. In the summer of 2005, Laura Ahearn, executive director of Parents for Megan's Law, criticized the registration system for its lack of uniformity and insufficient breadth; the classification of offenders into low-risk and high-risk categories is, to her, unsatisfactory. "You could live right next to a predator and have no way of finding out," lamented Ahearn (Kelly, 2005), once again boldly asserting the equivalence of committing any sexual offense with 'predation'. Ahearn is also notable for her insouciant response to the death of Justin Fawcett, arguing that: "Every single state has an age-buffer law. A minor is a minor, and that's why you have laws to protect them" (Householder, 2004). Evidently Ms. Ahearn is unaware that Michigan's "age-buffer law" (assuming that by odd word choice she is referring to what is sometimes called the "Romeo and Juliet" provision, aimed at protecting teens in consensual relationships) is not applicable in offenses involving sexual penetration-or else believes that her audience is unlikely to know that or to bother finding out. After the Lunsford and Bruschia murders in Florida and the Groene murders in the Northwest, the media pressure on politicians to intensify efforts against all sexual offenders, regardless of offense type, increased. Entertainer Oprah Winfrey, who commands a considerable degree of credibility with the American public on the issue of sexual abuse despite a lack of any known expertise in either the criminal or psychological fields, has adopted it as a flagship cause, slapping bounties on the heads of fugitives and declaring "We are going to move heaven and earth to stop an evil that's been going on far too long." Oprah Winfrey's online site includes one of the most bizarre features this author has come across for identifying possible "sex offenders"-a list of traits vague enough to identify anyone or no one, e.g. "Adults your children seem to like for reasons you don't understand." It should be mentioned that this list of "sex offender" traits is included as a feature on the "child predator watch list", once again improperly identifying the two categories (Harpo Productions, 2005). One might be tempted to argue that this is merely the most recent example of the prudent mean between carelessness and paranoia eluding Winfrey as it has on other issues (mad cow disease, for instance) except that on this issue it has eluded the rest of the country as well. The only arguably positive development in recent years is a paradoxical one. The U.S. Department of Justice (2005) has reported that the number of registered sexual offenders in the United States now exceeds 500,000. With so many otherwise productive citizens having been essentially stamped as dangerous predators-and many having been harassed and ostracized, or worse-a number of them and their family members have become sufficiently radicalized by the experience to become politically active (many have little left to lose by doing so, for reasons already noted.) Organizations representing registrants and seeking to reform or end Megan's Law have begun the arduous process of lobbying state legislators. The superb lobbies SO Hopeful, the Sex Offender Support and Education Network (SOSEN) and the Coalition for a Useful Registry (groups originating in Oregon, Florida and Michigan respectively) have had some degree of success in fighting especially draconian measures proposed by the legislature, and have worked toward educating the public as to the unintended negative effects of notification laws and providing community support to registrants and their families. Without efforts like these, our nation is likely to experience more recidivism, more suicides, more homicides, and more needless incarceration. It's time to deal frankly with the facts. Paranoid schemes such as public registration have been given their chance and have failed. The need for reform and for a common sense discussion of sex-related crime has never been greater, as the stakes have never been so high for so many Americans. And the only way to achieve reform that counts is to demand an end to the greatest monument to political demagogy and media fear-mongering in recent memory. Repeal Megan's Law. Bibliography Associated Press (2003). Defendant screams in court after innocent plea in Geoghan prison killing. Retrieved Nov. 11, 2005, from Boston.com Web site: http://www.boston.com/news/local/massachusetts/articles/2003/09/19/defendant_screams _in_court_after_innocent_plea_in_geoghan_prison_killing/. Associated Press (2005). Teen mother ruled a sex offender. Retrieved Feb. 2, 2008, from cerius.org Web site: http://www.cerius.org/ref/YouthPred/20051231-KUTV-TeenMother.htm Bureau of Justice Statistics, (2003, November). Recidivism of Sex Offenders Released from Prison in 1994. Retrieved February 2, 2008, from U.S. Department of Justice Web site: http://www.ojp.usdoj.gov/bjs/pub/pdf/rsorp94.pdf Carey, C. (2005). Banishment is not the answer. Retrieved Nov. 1, 2005 from Human Rights Watch Web site: http://hrw.org/english/docs/2005/02/02/usdom10106.htm Christenson, T. (2004). Accused teacher dies from hanging. Battle Creek Enquirer. Retrieved May 25, 2005, from http://www.battlecreekenquirer.com/news/stories/20040608/localnews/595940.html Dodd, V. (2000, July 24). Innocents suffer when law of the lynch mob takes hold. Retrieved May 9, 2006, from Guardian Unlimited Web site: http://www.guardian.co.uk/print/0,3858,4043662-103690,00.html Ellison, M. (2000). How Americans responded to Megan's law. Guardian Unlimited. Retrieved Nov 03, 2005, from http://www.guardian.co.uk/child/story/0,7369,351435,00.html Freeman-Longo, R.E. (1996) Feel good legislation: Prevention or calamity. Child Abuse & Neglect, 20 (2), pp.95-101. Freeman-Longo, R.E. & Blanchard, G.T. (1998). Sexual Abuse in America: Epidemic of the 21st Century. Brandon, VT: Safer Society Press. Freeman-Longo, R.E. (2002). Revisiting Megan's law and sex offender registration: Prevention or problem. In Hodgson, J.F. and Kelley, D.S. (eds). Sexual violence: policies, practices, and challenges in the United States and Canada. Praeger Publishers, Westport, CT. Garfinkle, E. (2003). Coming of age in America: the misapplication of sex-offender registration and community-notification laws to juveniles. California Law Review, 93(1), 163-206. Giles, D. (2005a). A time to kill. Retrieved Nov. 20, 2005, from Townhall.com Web site: http://www.townhall.com/opinion/columns/douggiles/2005/04/23/15210.html Giles, D. (2005b). A time for anger: porn, pedophiles and your kids. Retrieved Nov. 20, 2005, from Townhall.com Web site: http://www.townhall.com/opinion/columns/douggiles/2005/11/06/174481.html. Goffard, C. (2002). Sex offender's past stalks him. St. Petersburg Times Online. Retrieved Oct 16, 2005, from http://www.sptimes.com/2002/05/19/news_pf/Hillsborough/Sex_offender_s_past_s.shtml Goffard, C. (2003). Child molester to return to prison. St. Petersburg Times Online. Retrieved Oct 16, 2005, from http://www.sptimes.com/2003/08/01/news_pf/Hillsborough/Child_molester_to_ret.shtml Gunderson v. Hvass (2003) 339 F.3d 639 (8th U.S. Circuit.) Hanson, R. K. (2001). Age and sexual recidivism: A comparison of rapists and child molesters. (User Report No. 2001-01). Ottawa: Department of the Solicitor General of Canada. Harpo Productions, Inc., (2005). Oprah's child predator watch list. Retrieved Nov. 20, 2005, from Oprah.com Web site: http://www2.oprah.com/presents/2005/predator/predator_main.jhtml. Hayes, J. (2005). Murder shows need for civil confinement. Niagara Gazette. Retrieved Nov 3, 2005, from http://niagra.cnhiindiana.com/story.asp?id=2794 Householder, M. (2004). Michigan legislators attempt to alter state's sex offender registry. Retrieved Dec. 01, 2005, from SignOnSanDiego.com Web site: http://www.signonsandiego.com/news/nation/20040503-2321-youngsexoffenders.html. Huus, K. (2007, April 20). Reading between Cho's lines. Retrieved February 2, 2008, from MSNBC Web site: http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/18221031 Joyce, T. (2004, Aug 21).Sex offenders create legal enigma; A York case is upheld as an example of recidivism hurting efforts to rehabilitate. York Daily Record, pp. 3/05. Kelly, K. (2005). To protect the innocent. U.S. News and World Report, 138(22), 72-73. Kentucky Community and Technical College System, (2005). Today's news for August 23, 2005. Retrieved Oct. 21, 2005, from KCTCS Web site: http://www.kctcs.net/todaysnews/index.cfm?tn_date=2005-08-23. KMBC-TV, (2005). Some say Missouri's sex offender registry flawed. Retrieved Nov. 19, 2005, from TheKansasCityChannel.com Web site: http://www.thekansascitychannel.com/news/5340859/detail.html. Kunkle, F. (2005). Court overturns child porn conviction. Washington Post.com. Retrieved Oct 01, 2005, from http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp- dyn/content/article/2005/09/07/AR2005090702067.html Lanning, Kenneth V. (2001). Child Molesters: A Behavioral Analysis. 4th ed. Alexandria, VA: National Center for Missing & Exploited Children. Levine, J. (2002). Harmful to minors. 1st ed. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press. Lotke, E. (1997, Sep/Oct). Politics and irrelevance: community notification statutes. Federal Sentencing Reporter, 10:2. Retrieved Nov 3, 2005, from http://www.ncianet.org/stories/polnirr97.html. Megan Nicole Kanka Foundation (2005). Our mission. Retrieved Nov. 22, 2005, from http://www.megannicolekankafoundation.org/mission.htm. Milloy, R. E. (2001). Texas judge orders notices warning of sex offender. Retrieved Oct. 02, 2005, from Crime Lynx Web site: http://www.crimelynx.com/sexsign.html. Perez, M. (2005, November 22). Reports may shed light on Couey case. Retrieved June 16, 2006, from Ocala.com Web site: http://www.ocala.com/apps/pbcs.dll/article?AID=/20051122/NEWS/211220320/1001/news01 Reed, T. (2005, September 14). "Florida couple pleads no contest to abusing adopted children." Retrieved February 2, 2008 from the Associated Press via the Billings Gazette, at http://www.billingsgazette.com/newdex.php?display=rednews/2005/09/14/build/nation/88-adopted-kids.inc Schneider, A., et al. (1998). Children hurt by the system. Retrieved Dec. 2, 2005 from Seattle Post-Intelligencer web site http://seattlepi.nwsource.com/powertoharm/therapy.html U.S. Department of Justice, (2005). Department of Justice links New Hampshire. Retrieved Dec. 04, 2005, from 2005 OJP Press Releases Web site: http://www.ojp.usdoj.gov/pressreleases/BJA060015.htm. Vigilantism threatens community notification. (2005). News Tribune. Retrieved Sep 21, 2005 from http://www.thenewstribune.com/opinion/story/5170956p-4701985c.html Zevitz, R. et al. (2000). Sex offender community notification: Assessing the impact in Wisconsin. Retrieved Nov. 30, 2005 from National Institute of Justice web site http://www.ncjrs.org/pdffiles1/nij/179992.pdf Zimring, F. (2004). An American travesty: Legal responses to adolescent sexual offending. 1st ed. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. |

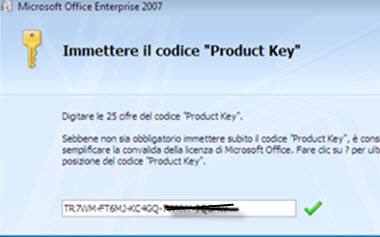

Image of ms office 2007 product key

ms office 2007 product key Image 1

ms office 2007 product key Image 2

ms office 2007 product key Image 3

ms office 2007 product key Image 4

ms office 2007 product key Image 5

Related blog with ms office 2007 product key

- nayminkhit.blogspot.com/...လိုအပ္ရင္ သံုးလို ့ရေအာင္ တင္ေပးလိုက္တာပါ. ms office 2007 professional & Ultimate & Enterprise မ်ားရဲ ့ Product Keys မ်ားျဖစ္ပါတယ္. အျမဲတမ္း update ျဖစ္ပါတယ္. အသံုးလိုတဲ့...

- tukangnggame-indonesia.blogspot.com/...Enterprise $59.00 at ... MS Windows Xp pro Sp2 + Office 07 (Today Only) Microsoft...Unlimited Installs PRODUCT KEY INCLUDED FULL...Microsoft Office Access 2007, Microsoft Office Excel...

- unlockforus.blogspot.com/... the Microsoft Office 2010 Product Key? I talked to one of the people...I’m going to give you the MS Office Home and Student 2007”. Looking at the retailer version...

- shine.yahoo.com/blogs/author/ycn-1411977/...keys stored remove invalid ms office 2003 office 2003 discount microsoft office student 2007 product key french patch microsoft office 2003 office 2003...

- unlockforus.blogspot.com/...Summary Information has been updated - Getting the Product Key of Office 2007 conflict with MS Visual Studio Web Authoring Component Thanks to CNET.com for...

- shine.yahoo.com/blogs/author/ycn-1411977/...hate the office 2007 ribbon i lost my microsoft office 2003 product key office 2003 standard...unable to save ms office 2003 ...goldmine microsoft home office 2007 product key microsoft office...

- evoice.wordpress.com/... for the new office products starting in the Fall 2007. Keep an eye on your... dates for MS Office 2007 and more. Key features of Office...

- supremophantom.blogspot.com/...Activation Crack [ psswrd: SupremoPhantom ] for MS-Office 2007 with SP2 , so I have shared the...SP2 already installed and have a product key as well, and now all you are...

- shine.yahoo.com/blogs/author/ycn-1411977/...microsoft office professional plus 2007 auto insert product key in office 2007 ea nhl 2004 gm office download office professional...office 2007 fix patch restore classic task bar ms office 2003 for dummies ...

- shine.yahoo.com/blogs/author/ycn-1411977/...2003 microsoft office 2004 word microsoft office access 2003 runtime download ms office 2007 information i need a office 2003 product key code office 2007 for students microsoft office 2003 will not...

Related Video with ms office 2007 product key

ms office 2007 product key Video 1

ms office 2007 product key Video 2

ms office 2007 product key Video 3